I was working in the emergency department (ED) some time ago, and one of my colleagues asked me to examine their shoulder. The ED is known for the chaos that can happen at any given period. Though, at times when it settles down, co-workers will occasionally ask me about orthopedic problems that they are experiencing. I don’t have time to do a thorough eval with them, so I usually spend a scattered 5-15 minutes throughout the 12-hour day for a focused H&P. Colleagues are sometimes curious when I’m examining a co-worker, as not everyone knows my background as a physical therapist (PT). I’ve had numerous encounters like the one mentioned above. In the last several years, I have received perplexing comments, many of which surprised me:

Co-worker 1 (RN): What do PTs do? They mostly massage, right?

Co-worker 2 (RN): So you’re a PT? Is that a bachelor’s degree?

Co-worker 3 (RN): You stretch people right? What type of stretches should I do for my knee pain?

Co-worker 4 (RN): PTs can prescribe medication in the military? Are you sure about that? Is that safe?

Co-worker 5 (RN): Why do PTs need a doctorate for the type of work that they do? Are patients that complicated?

Co-worker 6 (MD): The patient in room 5 has clonus? Are you sure? The neurologist’s recent H&P doesn’t say anything about him having that.

Some comments were a breath of fresh air, and quite encouraging:

Co-worker 7 (RN): Do you think you could evaluate my left shoulder injury? I went to my primary care physician and they have no idea what the hell is wrong.

Co-worker 8 (PA): hey, as a PT, would you recommend getting an x-ray for the knee with this type of injury?

Co-worker 9 (DO): I think this guy might have an upper cervical ligamentous injury. What do you think given his symptoms?

Co-worker 10 (NP): What would be your diagnosis for that 35 y.o. patient with low back pain?

Believe or not, every single comment was made by an RN, PA/NP, or MD/DO. These were my own colleagues! I ignorantly used to think that a PT’s skill was common knowledge. However, after being in healthcare for 8 years, I realize that our profession has siloed itself from a large majority of stakeholders that make up the interdisciplinary team. While PTs are not entirely to blame, much of it is our own doing. I have found that a large majority of PTs focus their time and efforts on topics related to their own niche: manual therapy, exercise, physical activity, resistance training, pain science, etc. If you go on twitter, you’ll easily discover all the bickering that goes on between PTs all across the world. Rather than concentrating on policy reform or having productive conversations that would strengthen the profession, many focus their efforts on demonizing manual therapy (ex. joint manipulation, dry needling, etc.), attacking the pharmaceutical industry, blasting rehab study methodology, arguing about the nuances of pain science, and disagreeing about minute details of research articles. They’re too busy publicly puffing themselves up and putting others down. Their ego and narrow-mindedness is on full display, and frankly, it’s embarrassing. Many PTs preach to their own choir, not knowing that their ideas lifelessly bounce around in their own echo chamber. It’s no wonder that our profession is slow to obtain direct access and recognition across all 50 states. We are not unanimously considered as the clinician of choice for conservative musculoskeletal care…and for good reason. If we spent half as much time on other important matters, we’d be the practitioner of choice.

While these issues aren’t inherently bad, they tend to detract from major professional issues: improved autonomy, increased scope of practice, better reimbursement, and the cost savings of seeing a PT. I don’t see the same issues within the nursing and medical profession (they have their own unique problems, but this isn’t one of them). While I do believe the PT profession is siloed, we’re not exactly alone. I was surprised by the number of orthopedic physicians on Twitter who recently conceded that they knew little to nothing about rehabilitation. For many orthopedists, that’s a tough pill to swallow. In the PT world, it’s commonplace for PTs to attend lectures and in-services by orthopedists. Rather than making it a one way street, a physician mentioned that he attended PT in-services so that he could strengthen his own knowledge about rehab. That’s mutual respect. That’s inter-professional education. Outside of orthopedists, sports medicine physicians, athletic trainers (ATC), and strength coaches, most team members don’t have a clue as to what we’re capable of. Even the aforementioned members above can sometimes be oblivious, and that’s saying something considering we interact with them the most.

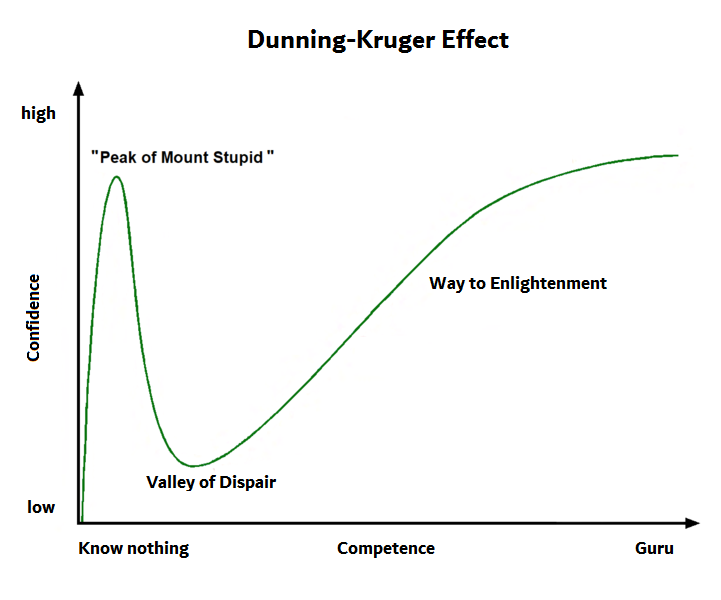

I am a strong believer that inter-professional education should start in academia. It takes a team to care for a patient, and often times, our teammates don’t even know the roles of their own members. I can confidently say this, as I’ve had experience in outpatient orthopedics, inpatient acute care, the emergency department, urgent care, and primary care. In every single setting, there was at least one clinician who was surprised by my expertise as a PT. Should our knowledge come as a surprise? Should our own team members be shocked by our skill? Or should that be the expectation? Childs et al. (2005) conducted a qualitative study to compare orthopedic knowledge between various healthcare professionals. They discovered that orthopedists scored the highest on the exam followed by board-certified PTs. This comes as a shock to some people when it really shouldn’t be surprising at all. One reason this happens is because there is often no exposure or collaboration in the graduate setting to other team members. Sometimes the first encounter with a PT is when our team member is personally injured and needs rehab from a therapist! This should not be the first encounter with a PT! We must leverage our expertise and teach each other. We must utilize each other’s strengths so that we can strengthen our own weaknesses. These issues illustrate the Dunning-Kruger Effect very well:

(Wikipedia, 2020)

The path to enlightenment is understanding and acknowledging that you cannot know everything. It doesn’t matter if you’re a physician, nurse, nurse practitioner, physician assistant, pharmacist or physical therapist. Complete arrogance leads to complete stupidity, both in the eyes of your patients and your peers. Complete stupidity leads to mistakes. And sometimes these mistakes can be costly. When we reach the valley of despair, we must realize that the medical world is bigger than our own bubble. It’s bigger than any one profession. It’s bigger than any one style of training. One way to enlightenment, along with a dedication to lifelong learning, is leveraging expertise within and outside of your profession. There is no way around it. Only leveraging expertise within your own profession leads to echo chambers and incomplete perspectives. You will end up thinking you know more than you do. That’s a grave mistake. You will not get the 10,000 ft view by doing that. My family physician colleagues leverage my orthopedic expertise, and I leverage their family medicine expertise. We’re both better for it. Dr. Jordan Peterson, PhD, a clinical psychologist, touches on this subject. He states that when we are having difficult conversations with other people, you should “assume people might know something you don’t.” This applies to daily conversation as much as it does when collaborating with colleagues. Take pain science curriculum for example. Dr. Durbhakula from John Hopkins reports that medical students, on average, receive about 9 hours of formal pain science curriculum (NPR, 2019). Conversely, PTs, on average, have approximately 31 hours of pain science curriculum, and can have as many as 115 hours (Bement & Sluka, 2015). That is more than double the pain science curriculum in medical school. Not surprisingly, physicians do not often realize this disparity. If you don’t know the disparity exists, you may be less likely to refer to a PT for pain management. This is a problem when you consider the current opioid epidemic that exists in our country. The reverse is equally true for a plethora of topics that PTs do not cover in school. Please do not misunderstand me: this is not a knock on physician training. Physicians receive the greatest number of hours of clinical training compared to any other profession. They have the most well-rounded curriculum. The point is that we have to better understand each professions’ strengths so that we can take full advantage of it for the betterment of our patients. We do a disservice to our patients when we don’t understand the breadth of knowledge that our other colleagues have.

If you open yourself up to learning about what other people know, you’ll better understand your own knowledge deficiencies. We are all prone to the Dunning-Kruger effect. We’ve all experienced it at one point or another. It’s not a linear path; sometimes we catch ourselves on top of mount stupidity and have to stumble back onto the road of humility. All of these examples highlight the importance of professional collaboration among different team members in healthcare.

In summary…

-Academic programs should actively recruit team members outside of their own profession and leverage their expertise in the classroom. This will better serve the team and our patients.

-When you’re on the job, seek out learning opportunities from team members outside of your profession. Try to better understand their knowledge and skill. Soak it in like a sponge and apply it to your daily practice.

-Pride comes before the fall. Never let arrogance blind you from the reality that other people know things that you don’t. Each team member brings something special to the table.